Point Grey Foreshore: Past presents and imagined futures

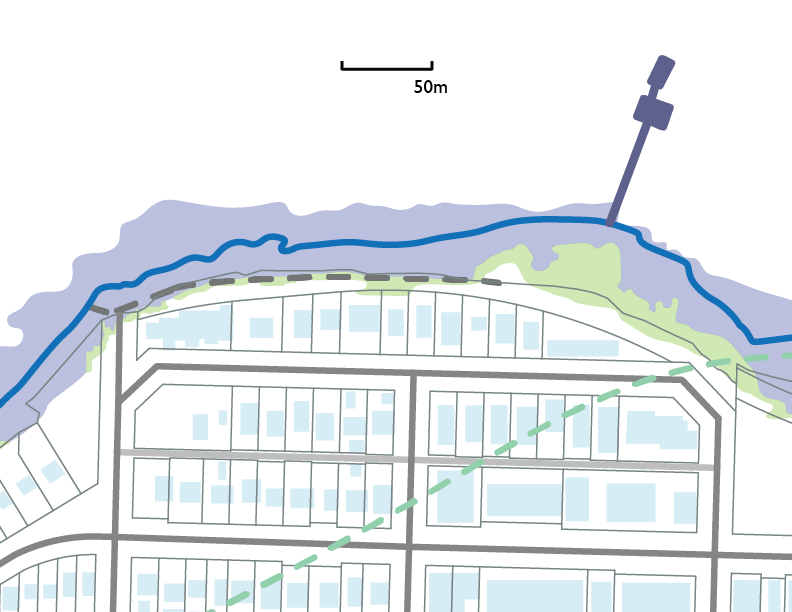

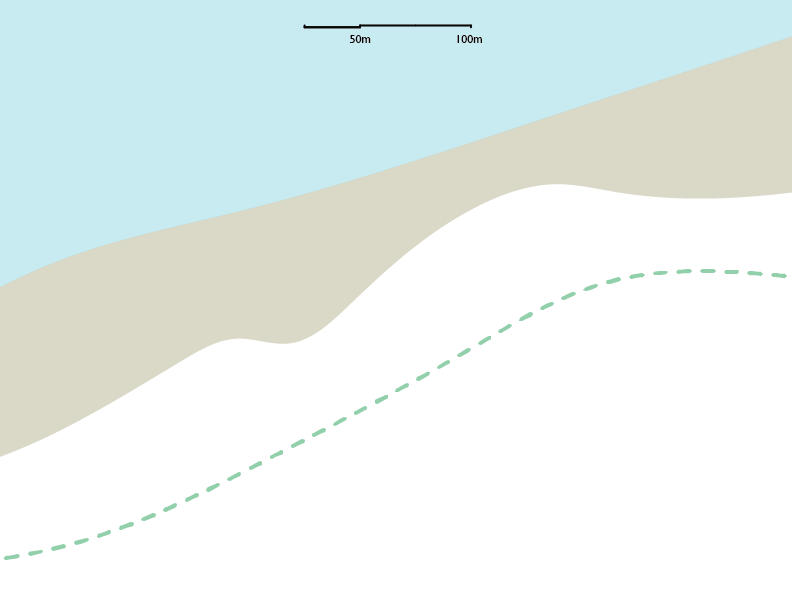

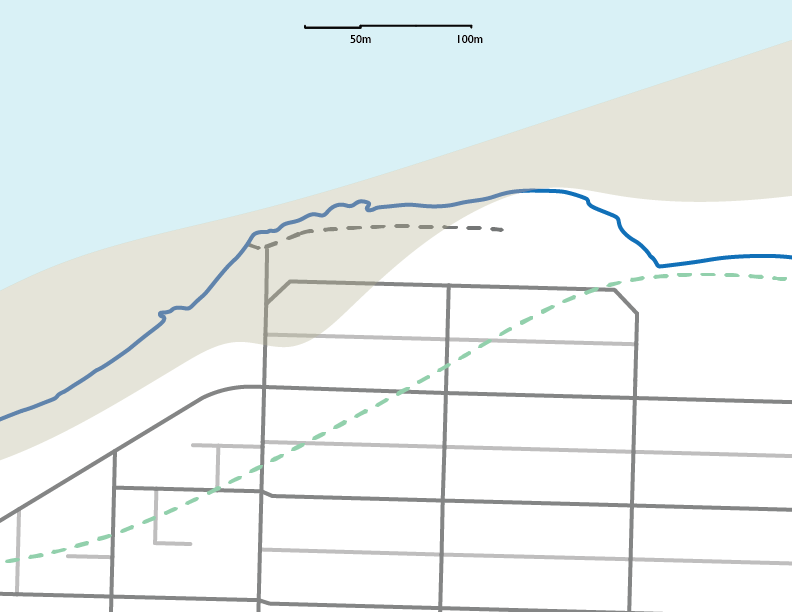

The maps I made for my presentation yesterday on my site at the Point Grey Foreshore near Kits Beach. The first is the indigenous use of the site pre-colonialism, then the street grid, lot lines and buildings. Next is flood predictions for climate change.

I have three artifacts

1.

A dashed line on a map representing what was here before Europeans arrived.

A trail that was compacted by the repeated passage of human feet. It was selected based on topography, the condition of the land and the needs of those passing through.

It was a trail selected by the desires and instincts of humans rather than the needs of commodification and measurement. It was collectively accessible and enjoyed.

2.

Second, the present through a more recent past, a colonial past, embedded in the shape that our streets, sidewalks and buildings take. A past that is inescapable in Vancouver and defines the form the trail takes today.

This is land that was parceled off. Right angles replaced the desire line. It was to be bought and sold, owned by individuals rather than something that was for all of us.

3.

A map prepared by the City of Vancouver about the future. It accesses flood risk due to climate change up to 2100.

It tells me that the foreshore and trail will be radically different in eighty years. Flooding will be far more frequent.

The trail and other areas making up our valuable public waterfront are under shapes telling me that more and more often they will be inundated until they are ultimately submerged.

Assuming nothing changes in their design and elevation.

Next slide

1.

First, this is a map from Visual History of Vancouver by Bruce MacDonald. It was published in 1992 and predates much of the mapping technology we use today. I accessed it online as an e-book rather than as a physical object. The map is less precise than the other two. I don’t know how much to trust the exact locations of the shoreline and trail but I’ll take his word for it.

In laying the trail over maps from today I am surprised to find that it is further back than I’d imagined it would be. Without the roads and form of today’s city it’s hard to place the features depicted by the map.

Next slide

During the time between when the glacier receded at the end of last ice age, leaving behind it the stunning landscape of the Burrard Inlet, and when European settlers arrived, Vancouver was home to the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples (Berelowitz, 2005).

They did not live on this site but there were waterfront villages in what is today False Creek. A notable one was at the current location of Granville Island (MacDonald, 1992).

This trail would have been a connector for those living in nearby villages as well as passing through the region.

It was selected and marked by the movement of feet passing along it, compacting the ground and restricting the growth of vegetation. Selected not by the lines of the grid but by the conditions of the landscape and what route made the most sense.

The trail and the land around it would have been collectively held. The UBC Indigenous Foundation writes, “Most First Nations did not believe that pieces of land could or should be owned by individuals—humans, along with all other living beings, belonged to the land. The land provided for humans, and in turn, humans bore a responsibility to respect and care for it. Many Aboriginal peoples understand this as a reciprocal relationship with the land. European settlers arriving in North America brought with them concepts of private property ownership, and the notion that humans could, and should, own land” (2009).

Vancouver is a heavily gridded city. Straight lines and right angles abound. They were a great way to buy and sell, to commodify and trade land.

In City on a Grid, a history of New York’s grid, Gerrard Koeppel writes, “The grid favours private interest over public convenience. The right angle values its interior space. Diagonal or nonlinear routes – dirt footpaths through an empty lot, curvilinear forms traversing natural topography – celebrate public space, the civic interest” (2015, xv).

Next slide

What we now think of as Vancouver, the street grid and lot lines, were created by imperial acts of measurement. The forest and waterfront were measured and divided using a device known as the chain. 66 feet or 20m long, the length and depth of blocks as well as the width of streets was derived from this unit of measurement (Berelowitz, 2005).

Next slide

In Dream City Lance Berelowitz writes, “The streets devised by the Royal Engineers and CPY surveyors was a highly effective, if somewhat crude way of subdividing raw land. It reflected the unsentimental military mindset of the British colonial imperative. Variations of it had worked across the Empire, wherever the British had set up shop in new territory. What it lacked in grace or sublety it more than made up for, in its authors’ minds at least, in its promise of commercial efficiency” (2005, 60)

Next slide

This act of surveying was largely an act of obliteration. Of forests, of trails, of past ways of using and accessing land.

There are a few remnants that break the grid.

Kingsway is a prominent example. It was the original trail used by indigenous folks that followed the “ridge line of the hilly landscape” from East Van to New West (Villagomez, 2008). It was retained and incorporated into our streets.

Next slide

2.

This recording is taken at one of the spots where the historic foot trail crosses with a place that is publicly accessible. Mostly it runs through lots and buildings but in this spot it intersects with a road and sidewalk, somewhere I can go without trespassing. Somewhere I can sit for a while and not be asked to leave.

Next slide

This spot is less peaceful than the trail. The sound of vehicle traffic is loud and noticeable. I can also hear people running and jogging. Their feet pad against the smooth and solid sidewalk. I can only hear the texture if someone is dragging their feet. I can also hear bikes and the rustling of the wind.

4.

My second artifact is a Google Maps satellite image embodying the condition of the site today and with it the street grid, lot lines and buildings that are a product of colonial surveying (Google Maps, 2019).

One of the waterfront homes on Point Grey Road recently sold for $12,300,000. Another further west on Point Grey Road sold for $17,800,000 (Zealty, 2019).

I cannot enter these yards, these homes. They are worth a great deal. They are a roaring success if your goal is to commodify land.

The map is finer and more precise than the previous map. I can zoom in and out. I can see many details of the site including the condition of the rocky natural beach and how it appears in the water. For me it encapsulates the changing nature of my site, the coming and going of tides, better than other current maps.

The first map recording the precolonial condition of my site reflects the tidal nature of the waterfront. It uses a separate colour to mark an area that would be shifting and changing. The satellite image doesn’t do this but does show the water, the path and the foreshore in a way others do not (Google Maps, 2019; MacDonald, 1992).

Next slide

5.

The only thing we can be certain of is change. We especially live in an era of rapid change and chaos. Our world is burning and there is an opportunity to critically rethink the way we have built our societies and the world around us.

My third and final artifact speaks to the future. It was prepared for the City of Vancouver by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants in 2014 to access future flood risks to 2100. A 1m sea level rise is predicted.

I personally think that’s a bit conservative but for the purposes of this assignment I’ll go with it.

Next slide

I have a final recoding taken from the bench closest to the east end of the trail.

The trail and beach have an uncertain future that includes increased frequency of floods and erosion. In the future, if nothing changes these spaces could become inaccessible. As the water rises less and less of the foreshore will be accessible to humans. The trail will face the risk of erosion and damage during flooding and king tides.

It’s still not accessible, another choice, another problem.

Perhaps if we claim some of the space currently occupied by those expensive homes, we could build an accessible and resilient place. Perhaps.

We are in the midst of a housing and climate crisis. There are costs to the choices we have made. All this individualism is hurting us and it’s hurting the planet. We need each other. We need our public spaces. We can’t go back but we are in a moment where we can make new choices about how the future unfolds.

The trail we have now isn’t the same as it was but it’s still there. It feels different than the road and sidewalk where I sat to make my recording.

For now, I love this space. I am drawn to it. I would add my voice to the assorted calls saying that this is a place worth preserving. The decision not to do something is as powerful as the decision to do it. We can learn from the problems created by past decisions and do something different. We must.

It feels nice to be there. It fills a need I have as a human and it fills a need lots of others have too. To gather, to be around vegetation, to listen to the sound of waves rolling in, to experience surprise, wonder, joy and rest. These things can’t be monetized but they are vital and we need them.

There is beauty in those dashed lines.

Bibliography

Berelowitz, Lance (2005) Dream City. D&M Publishers Incorporated.

City of Vancouver (2014) Coastal flood risk assessment Burrard Inlet flood depts not including freeboard: Scenario 3 - Year 2100, SLR 1M probability of 1/500. Vancouver.

City of Vancouver (2019) VanMapp. https://vanmapp.vancouver.ca/pubvanmap_net/default.aspx [Accessed 2019.08]

Google Maps (2019) Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps [Accessed 2019.08]

Koepell, Gerard (2015) City on a grid: How New York became New York. Da Capo Press.

MacDonald, Bruce (1992) Vancouver: A Visual History. Talonbooks.

Indigenous Foundations UBC (2009) Aboriginal title in Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/aboriginal_title/ [Accessed 2019.07.30]

Villagomez, Erick (2008) Vancouver’s deviant grids in Spacing. May 26. http://spacing.ca/vancouver/2008/05/26/vancouvers-deviant-grids/ [Accessed: 2019.07.30]

Zealty (2019) BC Real Estate Map in zealty.ca. https://www.zealty.ca/map.html [Accessed 2019.07.21]